Kirtland's Warbler 14 May 2010 Magee Marsh

How do you handle the paparazzi when you’re a major star and everyone wants a piece of you? Be polite, ignore them, eat your fill and be on your way.

Birders from all over the country are stalking our neck of the woods these days looking for, and enjoying, elusive wood warblers and other migrating species. We are fortunate to have, geographically speaking, a world-famous migrant trap only a couple hours from where we live. Magee Marsh in northwestern Ohio (aka for old timers as Crane Creek) is known throughout the birders’ world as the best spot in the country to see a majority of the members of the wood warbler family.

Our spot in Ohio has recorded 36 members of that family which numbers about 56 nationwide. Some species never reach the east or north; some are extinct. Since they all have wings, potentially, they could all join the party.

The rarest of these colorful birds is the Kirtland’s Warbler. It’s rare because it nests primarily, almost exclusively, in the Michigan jack pine forests. It’s endangered because of habitat loss and predation from Brown-headed Cowbirds. Kirtland's Warbler is dependant upon fire to provide small trees and open areas that meet its rigid nesting-habitat requirements.

The jack pine requires fire to open its cones and spread its seeds. The warbler first appears in a nesting area about six years after a fire when the new growth is dense and about 1.5 to 2.0 meters high. After about 15 years, when trees are 3.0 to 5.0 meters high, the warbler leaves the area. The female Kirtland's Warbler is more selective than the male in her choice of habitat, consequently, the best areas attract more females than males. The last residents of a tract that is getting too old are always unmated males. Sometimes guys are slow to figure these things out.

Because of its specialized home range and unique habitat requirements, Kirtland's Warbler probably has always been a rare bird. Scientists did not describe the species until 1851 when a male was collected on the outskirts of Cleveland. The species, eventually, was named in honor of Dr. Jared P. Kirtland, a physician, teacher, horticulturist and naturalist who authored the first lists of birds, mammals, fishes, reptiles and amphibians of Ohio.

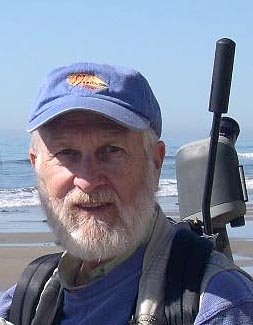

All of which brings us around to May 14 this year. Breeding male Kirtland's Warblers typically arrive back in Michigan from the Bahamas between May 3 and May 20. So, having one drop into our region at this time is something all of us birders wish for—but never believe will happen. Occasionally, we get lucky. And the odds are in our favor when you have some of the best eyes of the birding world on the lookout. We’re fortunate to have Kenn Kaufman, birding author and lecturer, living in our area. Kenn was checking the bushes that border Lake Erie at Magee Marsh on that morning when he found the bird.

Quickly, he was on the phone, and other lines of social networking communications, to tell the world that a Kirtland’s was in the neighborhood. It is also a happy coincidence that the Black Swamp Bird Observatory, headquartered at Magee Marsh, was sponsoring a major birding festival that had attracted thousands of birders, giving hundreds of people a look at this endangered species.

Bird's eyeview of the paparazzi

The bird proved to be more than just cooperative. It stayed in virtually the same bushes, eating bugs to fuel the rest of its trip to Michigan. It ignored the hundreds of photographers vying for the perfect shot, as well as the gawkers watching its every move. Like the best of stars, it kept about its business, knowing that in the morning it would be on its way, satiated and happy—just like all those photographers and bird watchers.

Kirtland's Warbler shows crowd his best side