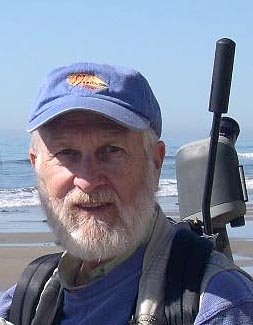

American Robin--with lunch.

Even when there never seems to be enough hours in the day, I still mange to find myself with time on my hands—like a recent afternoon, for example. I guess it was a combination of things: The recent Full Worm Moon, warm sunshine, three miles of walking and no sign of the bird I was looking for, and hunger.

I sat on the first available bench near the edge of Indigo Lake in the Cuyahoga Valley National Park and watched an American Robin search for worms. Earlier I watched a Song Sparrow carefully selecting bugs from the edges of the lake. The sparrow paid no attention to me as it moved from stick to stem, gleaning for bugs. After it passed I got down on my hands and knees, and tried to discern what it had been after. I could seen nothing.

The robin was a different story. I watched it pull a half dozen juicy worms from the ground, all within a two-square-meter area. How do they do that?

This is one of those questions birders can discuss at length. It ranks right up there with, “How do you pronounce Pileated Woodpecker, or, Northern Parula?”

I know, this is not like arguing about the state of healthcare (or lack thereof) in America. The mindset of a birder can best be compared with that of a teenager. We constantly, perpetually, live in a state of denial. We thrive on it, actually. No matter what evidence is brought forth, you stick by your gut feeling on any of the above topics.

I asked a few people about this robin-catching-the-worm thing. Some argue that the robin hears the worm. Others claim it sees the ground move. A third group is certain the robin feels movement through its feet.

I already had the non-answer. I looked at a number of reports and experiments and was able to find supporting evidence for whatever answer people wanted. Here’s a quick summary: Audubon’s Nature Encyclopedia offers a description of robins and their behaviors that concludes, after it rains, worms rest with just the tips of their bodies showing at the mouth of their burrows. This makes the worm an easy target for the bird.

Another study, done in the 1990s, isolated each of the robin's various senses. This study concluded that hearing is the most important sense. Apparently, the robin listens for the small noises a worm makes while burrowing along in the ground. Researchers noted, the robin does use its other senses too—watching for movement, feeling for rumbling with its feet. But the main sense that helps out the most is the robin's hearing.

The guy who seems to have more time on his hands than me to explore this subject was a Dr. Frank Heppner. This ornithologist suspected sight was the most important sense robins use to find worms. He did a whole lot of things to discover how a robin found its lunch. My favorite tactic of his was to drill holes in the ground that looked exactly like wormholes. Robins ignored the holes unless a worm was inside the hole within visual range. Whether that worm was alive and normal, alive but coated with a bad-smelling odor, or dead, the robins found the worms and ate them. He concluded that sight is the key sense robins use to find earthworms.

So there ya go; nobody’s wrong if everybody’s right. Get out in the spring weather and blow off an afternoon watching robins pull worms from the soil. You might learn something.

Song Sparrow--so many bugs, so little time.