Cuban Bee Hummingbird—the world’s smallest bird.

Trying to write about our recent bird research study in Cuba in 600 words--or less--is a fool’s task. I’ll just give you a few impressions—lessons—I’ve carried home. I have about 2000 images to edit, however, those can wait.

Susan and I were fortunate to participate in the Caribbean Conservation Trust’s study of endemic and migratory birds of Cuba from March 1 through 12. And although it was about Cuban birds, it’s impossible not to encounter politics. We read the suggested books beforehand and felt somewhat prepared. Lesson one: Don’t believe much of what you read about Cuba. The people we met looked at us in the same way we looked at them; both trying to see the horns, pointy tails and pitchforks of the other.

While our primary mission was bird surveying, we had ample opportunity to meet with and talk to kids and adults on the street. Lesson two: Cubans are highly literate. Kids go to school from 7:30 AM to 4 PM. Among their stated education goals is the challenge for all children to learn two languages besides Spanish.

It’s a mistake to hold an American measuring stick up to the physical structures, or infrastructure, of Cuba: Lesson three: The outside of a building might appear shabby (by our definition), however, inside you’ll find simplicity and comfort; lives free from the incessant need to have more. Yet, we kept wondering if they had enough …

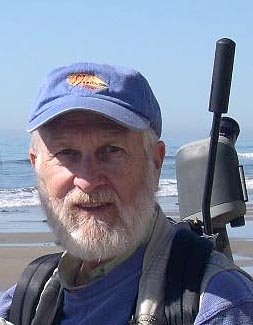

Orlando Garrido talks with us, surrounded by specimens of Cuba’s endemic birds.

We read that one thing people of Cuba appreciate about the current United States’ embargo is that it keeps Americans from visiting their country. Lesson four: Everywhere we traveled we were welcomed; into the home of Cuba’s premiere ornithologist, Orlando Garrido, in Havana as well as into the front seat of a proud kid’s beautifully restored 1956 Chevy in Playa Largo.

A 1956 Chevy in all its glory.

Not only would the birds we sought be different, we were gently warned that the people would be, too. In both cases this was true. Lesson five: The world’s smallest bird, the Cuban Bee Hummingbird is certainly a contender in the most glamorous category; people ride bicycles through city streets carrying sheet cakes—singlehandedly. Now that’s different.

It was noted that once we got away from the large cities, we’d experience the poverty of the land. Since our mission was surveying birds, we were away from cities most of the time. What we discovered was verdant rural farmland, unfamiliar crops, and roosters that begin crowing at 4 AM.