If I glance out and see no activity at the feeders, I’ll look around in the trees and often find him perched nearby. D.B. also likes to stand on our deck railing. I once saw him sitting atop the feeder array. This boy needs some education on hunting skills.

This morning as I headed for the trailhead in the park, I caught sight of a speeding bullet coming from my left. No, not a bullet. It was D.B. out to sharpen those hunting techniques. His target species was the resident flock of about 30 Canada Geese we tolerate. As he made his first pass, about 30 feet above the crowd, I noticed that the huge flock of American Crows that has been hanging around were also feeding among the geese. I’d guesstimate the crow flock at 100 birds.

D.B. passed over the gathering and not a feather moved. No one paid any attention. Whatever the geese and crows were feeding on held more promise than a death threat from something smaller than any bird in the crowd.

Undeterred, D.B. executed an inside loop and passed over again, this time about 15 feet above the heads of the ground feeders. That maneuver earned him a few looks and a couple honks.

Another return flip, this time right above the upraised heads of several geese. Now, a few feathers were ruffled. More honking, joined by some cawing from the crows, seemed only to encourage D.B., who has probably never whacked anything larger than a Mourning Dove. This time he reversed direction in a space no longer than his wingspan, diving on two of the more vocal geese. All I can figure is that they must have said something really nasty about his mother. I noticed his talons were not extended, however, I don’t thing the geese realized that. Both geese, using what they had learned in elementary school of how to duck and cover, hit the grass, chinstrap first.

D.B strafed the lot. His actions sent the crows packing in all directions. It looked like an explosion of black sand as birds, all vocalizing, sought shelter. Geese on the fringe of the action wanted no part of the little guy with the blue-colored back and pointy wings. They, too, took off in a thunder of applause, for which side I’m not sure. The two geese who were not able to keep their beaks shut, hugged the grass as D.B. leveled off and came to rest in a nearby walnut tree, now nearly devoid of its leaves.

Apparently training was over for the day. If geese can slink, that’s what the loud-mouthed pair did, talking to themselves or each other, they made their way 25 feet to the safety of the pond.

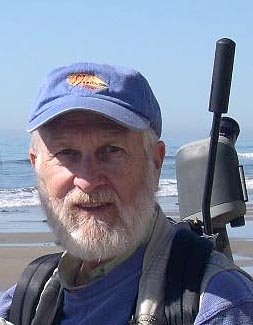

D.B. Cooper